Pharisee & the Tax Collector

Lazarus and the Rich Man

The Good Samaritan

The Prodigal Son

Sinning Out of Our Strengths

Being Surprised by Our Sins

An Attitude of Humility

In the previous posts, we have discussed what conscience is. And we may conclude it with a definition of conscience: conscience as a search for the loving thing to do.

We begin with this post on sin by defining sin as a failure to bother to love. If we use our conscience, or we search for the loving thing, and we choose not to do it, we sin. We fail to bother to love.

Notions of Sin & Humanity

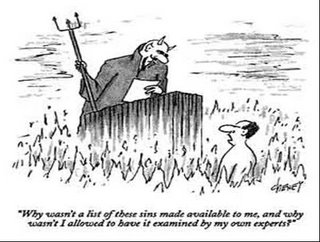

This definition points to us that the grammar school notion that sin is a crime is inaccurate. If sin were merely a crime it addresses more of the superego rather than our conscience. Moreover, viewing sin as a crime focuses more on the fear of being caught and the corresponding punishment.

The ultimate punishment then of someone sinful is to be sent to hell.

The ultimate punishment then of someone sinful is to be sent to hell.4th to 2oth Century

St. Augustine, St. Thomas Aquinas, and many others subscribe to the view of humanity as very sinful. We are liable to sin and thus, many are damned to eternal punishment and only a select few will go to heaven. This is known as massa damnata or mass damnation.

This view of sin and humanity is unhealthy because it creates a vindictive image of God: one who is interested more in punishment. This view underestimates God's mercy.

1970s to Present

After Vatican II, many believers swung to the opposite extreme known as massa bonna. People who subscribe to this belief think of humanity as purely good since man is created in the image and likeness of God. Man is thus seen as deserving to go to heaven since man's sinfulness is downplayed.

This too is unhealthy because it fails to acknowledge the presence of evil in the world, and makes humanity too complacent about its own faults.

We are sinners but loved.

The more balanced way of looking at humanity and sin is to acknowledge one's sinfulness and at the same time acknowledge God's loving mercy: to know that we are sinners but loved.

In fact when we see the words referring to sin such as adikia (wrongdoing), hubris (pride), or hamartia (missing the mark), we also find a partner word. That word is metanoia or a change of heart.

This only shows us that in our faith, sin does not have the final word, but it is the mercy of God that has the final word. That sin should always be viewed as an invitation to conversion.

How then do we judge whether an action is right or wrong? We need to consider the following:

- Intent - what is the goal of our action? what do we want to happen? It must be obvious that in order for an action to be good, the intention must be good. One cannot a good action with a bad intention!

- Means - how do we accomplish our goal? what do we do in order to reach that goal? Intention alone is not enough for us to judge whether an action is right or wrong. For example, scientist wants to look for a cure for cancer in order that he may save lives-however the only way he can do that is through life-threatening experimentation with 2 month old babies. Is that okay? Of course not.

- Circumstances

- Consequences

- Alternatives

- Subjective dimension. We say that an action comes from a person: an action is not without an actor.

- Thus we say that an action is a decision made by a person, and that person is changed and formed by those decisions. (For example, your decision to go to school today opened a number of possibilities for the day. Your decision to go to school also means that you are not at home, and cannot do certain things). We are thus limited and at the same time enriched by our decisions.

- These actions bear the stamp of our character to the extent that we have freely chosen these actions

- Objective dimension. Our actions have impact on the real world.

- Actions have consequences regardless of intentions

- It shows that human actions are not only personal but always interpersonal and social.

- Conscience as capacity - also known as the antecedent conscience. This shows our general hunger for the good—our capacity to recognise the good. Thus it is the state of our moral selves before we confront a problem.

- Conscience as process - also known as actual conscience. This is the actual process of moral reasoning when confronted with a problem. It shows that conscience is a search for what is right through accurate perception, a process of reflection, and analysis. This is achieved through the following steps.

- Gather relevant information - who is involved in the decision? who should be involved? what are the relevant circumstances? Are there any options? What are its short-term consequences? Long term?

- Identify the moral choice to make - What are the actual issues involved?

- Seek Counsel - Consult the "experts" or those who have gone through similar circumstances. Likewise, one should look at scripture and tradition.

- Reflect and Pray - Jesus himself reflected and prayed when he had to make big decisions. If conscience is a sanctuary then if we truly want to meet God, it is through prayer that we find out what His will is.

- Evaluate alternatives - Using the information gathered, the consequences of each option are weighed. Which is the most loving way?

- Conscience as judgment - also known as command conscience. This follows the search when one actually decides to act. It is a concrete judgment of what one must do in the situation. This makes the decision my own. We must obey our conscience then above all other voices in order to be true to myself. Our judgments thus help form (or deform) our antecedent conscience.

- We are thus obliged to follow our conscience. If conscience is our search what is right, not following your conscience is tantamout to choose to do wrong.

- Our judgments are good as the ground it was built on. Good judgments assume a well-formed antecedent conscience.

- It always a fruit of hard labour. Judgments should not be haphazard, but the result of prayer and discernment.

Kleingeld.

by Marc-Andreas Bochert. 14:56

O Branco.

by Angela Pines and Liliana Sulzbach. 22:00

Anino.

by Raymond Red. 13:00

Home Road Movies.

by Robert Bradbook. 11:43

Recall that Keenan says that conscience is a call to grow. In his book Moral Wisdom, he quotes scripture and the works of our early christian fathers to further illustrate it.

Scripture

Keenan says that the imagery in the bible show conscience as a movement. St. Paul for instance, show this in:

Philippians 3, 13-14. "...forgetting what lies behind and straining forward to what lies ahead, I press on toward the goal for the prize of the upward call of God in Christ Jesus."

Galatians 5, 7. "you were running well."

We can also recall many other stories in the Bible that clearly show one's call as a movement. Recall the magi and the star, the woman with the hemorrhage moving to touch the tassel of the cloak of Jesus, the paralytic to the roof, Zaccheus to the tree, and many others.

The Early Fathers

Keenan says that our early christian fathers take this even further. They assert that one must really try to become a better person or otherwise become worse. Here is a sampling of their works.

Gregory the Great. "Certainly in this world, the human spirit is like a boat foolishly fighting against the river's rush: one is never allowed to stay still, because unless one forges ahead, one will slide back downstream."

Bernard of Clairvaux. "To not progress on the way of Life is to regress."

St. Thomas Aquinas. "To stand on the way of the Lord is to move backwards"

Connors & McCormick continue by articulating what conscience is.

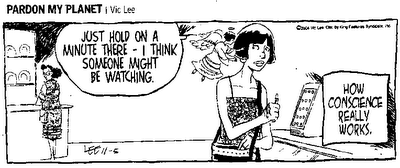

- a law and inner voice - since it is a law, it means that it ought to be followed. It is much like a command—but one that does not force itself upon us because it is our own voice. "Conscience is us as we struggle to discern and respond to the 'moral tug'"

- a search - we said that conscience is not an infallible moral code, because it is a process of finding out what the right thing to do is. It means that we do not have all the answers, and we admit out limitations, thus we look for answers. It means that conscience really is unfinished and dynamic.

Keenan (2004) furthermore elaborates that conscience is a call to grow. Thus, my conscience when I was eight years old is certainly different from my conscience now. We are called to become better and better people. - a sanctuary - a place where we meet God. Conscience does not impose itself on us; conscience is an encouter with God. Now, Miranda & Javier (2005) point out that cosncience is not God's voice within us. How then do we reconcile that with conscience being a sanctuary? We have previously said that conscience is a search. This means that we try to find out what it means to do right thing, but we do not exactly understand it. Our conscience is therefore erroneous. Our conscience at times, misunderstands what God actually wants. However, it does not negate the idea that conscience is our searching for what God wants for us.

- conscience is both personal and communal - God calls us as persons and communities. We can see this in scriptures: God calls Moses and Paul individually, yet this extends to entire communities. Although previously we acknowledge that conscience is an inner voice, we know that because we are relational, our environment, the people we love: our family, out friends also help form or deform our conscience.

Our past lessons concluded with love and conscience: we said that when we are faced with moral decisions, we try to find out what the loving response is. It is sometimes easy, but many times it is difficult to determine. It is our conscience that helps us discern how we can respond in a loving way. What is conscience then?

Our past lessons concluded with love and conscience: we said that when we are faced with moral decisions, we try to find out what the loving response is. It is sometimes easy, but many times it is difficult to determine. It is our conscience that helps us discern how we can respond in a loving way. What is conscience then?Let us first try to clarify what conscience is not. According to Connors and McCormick (1998), conscience is not:

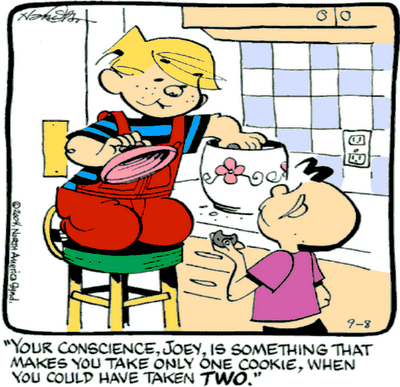

- A separate being. Conscience is not like a guardian angel that whispers to your ear tellling you what to do. It is neither Jimminy Cricket telling Pinnochio the right thing, nor is it the SafeGuard commercial that pops up here and there and commands you to buy a bar of soap. Our conscience is part of us.

- An infallible moral code. Conscience is not a list of things that are allowed and not allowed and shucked into your system like one would play back a DVD. Conscience continually changes and develops.

- A stern critical voice. It is not our superego that tells us not to run in front of moving vehicles or tells us to be nice boys and girls. It is not the fear that is evoked by the familiar words "isusumbong kita kay Mommy". The superego tells us "you shouldn't do that or you'll feel guilty.", conscience asks, "is it wrong?"

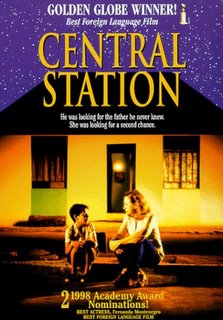

To highlight the lessons on conscience, I decided to show the film Central do Brasil to all of my classes. The film is a favourite of mine since it captures local colour as if you are transported to Brazil.

Synopsis by Sony Pictures, Inc. :

Every so often, a film unexpectedly appears from a remote corner of the world to capture the imaginations of audiences everywhere. When Walter Salles' "Central Station" was unveiled for the first time at this year's Sundance Film Festival, crowds embraced the film--with tears, with applause and with joy. A month later, it took the Berlin Film Festival by storm, winning the Golden Bear for Best Film and the Silver Bear for Best Actress for Fernanda Montenegro. For "Central Station" is that rarest of achievements: a film that speaks to your head while it touches your heart.

The film centers on a young boy (Vinicius de Oliveira) whose mother is killed in front of Rio de Janeiro's Central Station. Homeless and with nowhere to turn, he is reluctantly befriended by a lonely and cynical woman (Montenegro). Resisting her initial impulse to make a quick profit off the child, she commits to returning him to his father in Brazil's remote Northeast.

As buses and trucks carry the motley pair through the increasingly unfamiliar terrain, they defy their initial aversion to each other, journeying closer together and deeper inside themselves. Set against an epic backdrop of vast, majestic landscapes, the trip becomes a quest for their own identities: one boy's search for his father; and one woman's search for her heart.

Produced by five-time Academy Award-winner Arthur Cohn ("The Garden of the Finzi-Continis," "Black and White in Color"), "Central Station" introduces director Walter Salles to the ranks of the great humanist filmmakers. Using a simple and intimate structure, he has fashioned a profoundly moving tale of the triumph of the human spirit.